The robot economy and the new rentier class

It seems more top-tier economists are coming around to the idea that robots and technology could be having a greater influence on the economy (and this crisis in particular) than previously appreciated. Paul Krugman being the latest.

But first a quick backgrounder on the debate so far (as tracked by us).

Probably the first high-profile advocate of the idea — in recent times — that "technology and computers were changing the economy in weird ways" was Alan Greenspan in the 1990s, when he attributed a mysterious lack of inflation, high productivity and low unemployment rate to the arrival of a technologically rich "New Economy".

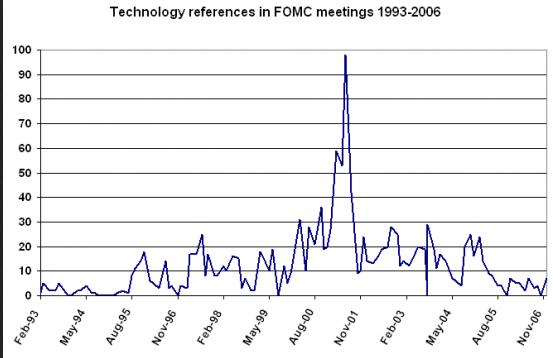

As we've written before, once the tech bubble burst — and Greenspan was supposedly proved so very wrong — the whole idea of technology being a fundamental force in the real economy was abandoned. This is well illustrated by the sudden fall in references to technology in FOMC meetings (as tracked by us):

Apart from a few fringe voices, the technology factor — and its likely effect on the natural unemployment rate as society moves towards a more leisure-focused framework, since all the hard jobs are done by robots and computers — became victim to a deathly silence in the world of serious economic thinking.

Indeed, when we first started considering the idea that technology could be behind the move to zero yields — with the crisis a function of technology shifts than anything else (especially if you follow the Keynesian view that one day a leisure economy becomes inevitable) — there was barely anyone out there to cite on the matter, apart from the Skidelskys and advocates of the Singularity movement.

There has been more commentary since then. George Magnus at UBS, for example, wrote a noteworthy piece in September.

But there has also been commentary to the contrary. Most notably there's the view set out by Robert Gordon (and Peter Thiel) that the crisis was a function of a lack of innovation and technology.

This concept caught the imagination of a lot of people, bringing technology's influence back to the forefront, while also reviving the whole idea of "limits to growth" and us being near that limit point.

Harvard's Ken Rogoff recently debated this point of view with both Thiel and Gordon, but seemed to arrive at a different conclusion. As his op-ed set out last week:

There are certainly those who believe that the wellsprings of science are running dry, and that, when one looks closely, the latest gadgets and ideas driving global commerce are essentially derivative. But the vast majority of my scientist colleagues at top universities seem awfully excited about their projects in nanotechnology, neuroscience, and energy, among other cutting-edge fields. They think they are changing the world at a pace as rapid as we have ever seen. Frankly, when I think of stagnating innovation as an economist, I worry about how overweening monopolies stifle ideas, and how recent changes extending the validity of patents have exacerbated this problem.

We feel this is a hugely important point. For what Rogoff is saying is that if we are experiencing technology stagnation, it's not because humanity has suddenly become less innovative. Rather, it's because incumbent interests now have the biggest incentive ever to impose artificial scarcity, which is stopping the speed of innovation.

Our own personal view is that this is because we've now arrived at a point where technology begins to threaten return on capital, mostly by causing the sort of abundance that depresses prices to the point where many goods have no choice but to become free. This is related to the amount of "free working" hours now being pumped into the economy — the result of crowd sourcing and rising productivity levels — thanks, in part, to the sort of gadgets that allow everyone to work anywhere and anytime, in a work environment that's generally speeding up as everyone tries to keep up with the competition by doing yet more hours voluntarily.

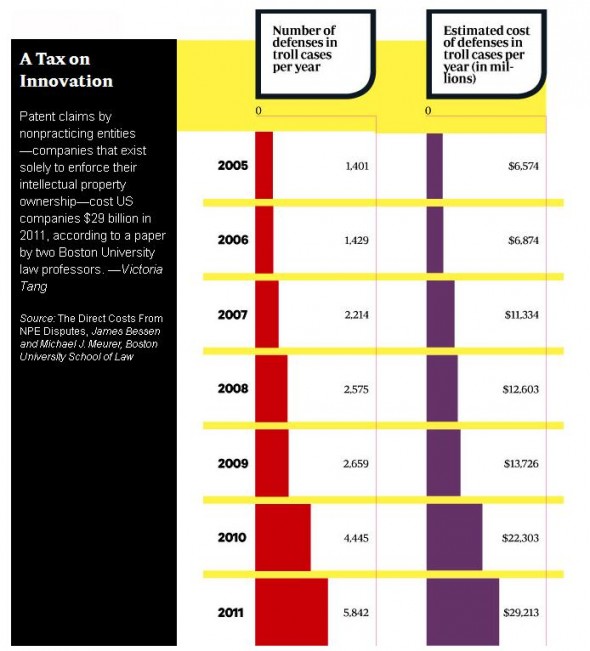

Patent wars, meanwhile… and the rise of companies whose entire raison d'etre is focused on protecting patents… is the ultimate counter force. As a recent Fed paper spelled out, there is real evidence to suggest that idea monopolisation has become a hugely counter-productive force in the economy.

We particularly enjoyed this opinion piece by Steven Levy at Wired Magazine on what he described as the emerging "patent problem".

As he explained:

The flaws of the patent system are most vividly exposed by the rise of trolls. The term, inspired by the stunted opportunists of myth, came from an Intel vice president who had been sued for calling a lawyer a "patent extortionist" and needed another expression. It refers to a company that doesn't make products but exists solely on the revenue of its patents. In the parlance of today's patent ecosystem, trolls are known as nonpracticing entities, or NPEs.

The rise of the patent troll effect, meanwhile, is well illustrated by the following Wired graphic:

Which brings us neatly to the latest offering on the technology factor, this time from Paul Krugman — who seems to have spent a large portion of the week thinking about the issue, with no less than two robot-themed postings.

But it's his last one which presents the monopolisation effect best, as he considers what's driving the share of non-farm business sector output downwards so rapidly:

But there's another possible resolution: monopoly power. Barry Lynn and Philip Longman have argued that we're seeing a rapid rise in market concentration and market power. The thing about market power is that it could simultaneously raise the average rents to capital and reduce the return on investment as perceived by corporations, which would now take into account the negative effects of capacity growth on their markups. So a rising-monopoly-power story would be one way to resolve the seeming paradox of rapidly rising profits and low real interest rates.

In our opinion that one paragraph explains today's reality perfectly.

So, robot and technology power is reducing the natural employment rate. But rather than our subsidising those who have lost jobs to technology, so as to spread that manna wealth that's literally dropped onto the surface of the earth at no-one's physical disadvantage, companies are using monopoly power to extort rents on the capital that is creating all that free wealth.

That's why inequality is rising.

As technology proceeds in a patent-obsessed world, the fruits of innovation flow to the owners of the capital and invention, forming a whole new rentier class. The financial assets/debts that back the innovation technology, meanwhile, get disproportionally valuable as their purchasing power gets completely out of whack with the output they radically accelerate.

If you think about it, inequality is always going to be the natural consequence of a technologically-driven deflationary environment. Whereas in inflation, those with financial claims (a.k.a money) are impoverished as their purchasing power is eroded, while those in debt are enriched — in deflation, those with financial claims (the result of increasing rentier flows, if Krugman's point is valid) become enriched as those in debt become increasingly impoverished.

In that sense QE and any move to "debase" financial claims is a move to dilute the wealth effect on legacy claims, which now claim a disproportionate share of available output, at least compared to what they did when they were created.

Low interest rates in many ways are thus only self-correction mechanism bringing the system back to balance — trying to offset the growing power of the innovation-based capital rentier class.

In that context it's understandable that the older the claim, the more preferable it is to hoard it, since the greater its claim over today's output. And in an environment where such claims are self-correcting anyway — via capital destruction brought on by negative rates, as people rush to invest in anything that gives them disproportional access to output and thus crowd each other out — that some of the rentier class see it logical to hoard in non-perishable assets "which cannot be debased" instead is an understandable consequence.

Related links:

Robots! No Robots! – FT Alphaville

Ahhhh! No robots! – FT Alphaville

The Patent Problem – Wired

Whose idea is it anyway – Towards a Leisure Society

Beyond Scarcity – FT Alphaville (series)

Peter Diamandis: Abundance is our future – Ted Talks

Sent from my iPhone