Magnus, on spending our way out of the Mumps

Mumps. A viral inflammatory disease. Or… the case of "most unusual monetary policies".

According to George Magnus of UBS, most of the western world has now been struck by the latter. And — contrary to popular belief — the disease is underpinned not by western profligacy, but possibly the very opposite phenomenon. Too much thrift. The want and need for too many savings in economies that demands spending on available capacity and goods today. It's a theme also being explored by Paul Krugman as part of his anti-austerity reasoning.

As Magnus explains in his latest research note, it is unlikely that mumps can ever solve the economic problem. At most, mumps can buy time until society realises the collective need to stop saving and start spending:

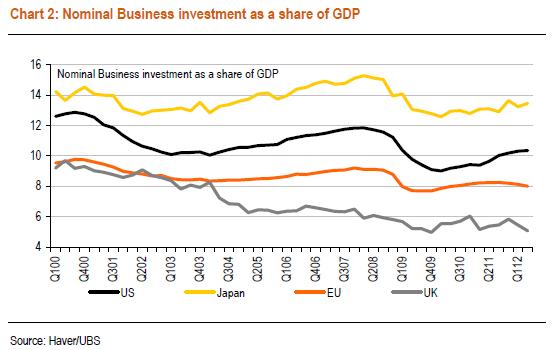

Second, down on the ground, mumps only work if the central bank can shift the private sector's preference for savings out of current income towards borrowing and spending. In a deep and protracted deleveraging, this simply cannot happen, at least on a sufficient scale. Generally speaking, the net financial savings of the private sector in advanced economies remain elevated or high, especially in the corporate sector. If mumps were going to have a galvanising impact on any sector, it should be on companies, which were and remain the only major sector with relatively low debt ratios. But despite, strong profits, good balance sheets, plenty of cash and the lowest borrowing rates in a generation, investment spending has continued to trend down (as a share of GDP), notwithstanding the bounce after the recent slump.

In other words, there is no point in being frugal.

Investment is and always will be the other side of saving. Culturally, we have become fixated with the idea that we need to save for our future. But there may be a solid economic justification for why those savings are yielding an ever lower return: society does not need us to defer spending the way we used to.

Ordinarily, via investment, deferred consumption is redirected towards consumption focused on boosting future output.

But the problem we arguably face today is that there is more demand for saving than there is opportunity for investment — at least the sort that can eventually yield a return that does not involve over-using the one thing the economy is truly constrained by: natural resources.

Which brings us back to the base money confusion and the misunderstanding about what "base money" is. As Magnus explains:

Third, the belief in mumps is based on the erroneous view that the creation of additional bank reserves, per se, will cause banks to turn them into new lending. As bank reserves rise, banks can lend more to one another if they choose, but that simply means that the money created by mumps stays locked in the banking system. What drives new loans is new sight, or demand, deposits and that's the outcome of economic activity. Replacing government bonds or other assets with reserves on the balance sheets of financial institutions, or changing the maturity profile of government bonds held in private portfolios does some things, but stimulating lending and spending isn't one of them. Nor, in the current environment, is creating inflation.

In short, the problem is not money availability but rather a lack of opportunities to deploy that money towards.

Think of it as the modern paradox of investment. We don't necessarily need investments in things that produce more stuff. Rather, we need investment in companies that produce the same amount of stuff only more efficiently — or more stuff with less resources. There's also the need to invest in big ideas, public infrastructure and utility projects, all of which are notoriously hard to squeeze profits out of.

It's possibly one reason why the corporate sector has become so margin obsessed.

And here's where the limits of growth debate comes in.

If there is a need in society, and a company moves to service that need, the company will usually derive a profit from filling that gap. (Unless it's infrastructure-based in which case it's about covering one's costs and ensuring enough income can be generated to maintain operations.) So it makes sense to redirect today's available capital, labour and output from an investor — who has no need for those things today, but believes will need more of those things tomorrow — to a company or entrepreneur, and reward the investor with additional output tomorrow.

Throughout history, bankruptcies have been caused by companies that were not able to keep those promises to investors in the future — mostly because the things they were making were less needed than anticipated.

With the resource constraint, however, you now also have to consider the "waste effect' on marginal utility — the degree to which demand for stuff detracts from available resources.

Yet there is another under-appreciated consequence of mumps — one that highlights its possible ultimate futility as well as its role in accelerating what could be the inevitable: its impact on savings.

Mumps, after all, is just as much about coercing people into spending today — rather than deferring spending until tomorrow — as it is about adding liquidity to the system. Central banks do this by effectively killing yield more quickly than the economy itself is killing yield. The point is to convince people that there is an ever greater opportunity cost in not spending today.

As Magnus notes:

Fourth, mumps may be harming the economy to the extent that low policy rates and bond yields are withering the savings side of the economy, even as people and companies want to save, at least in an ex ante sense7. They are certainly undermining pension plans, and giving corporate sponsors additional reasons to hold on to cash. And they may also be having adverse distributional effects across income groups. The first part of this is about the loss of interest income. In the US, for example, household interest income from assets has dropped to below $1 trillion, compared to $1.4 trillion in 2008. That $400 billion drop is equivalent to a fall from 11.5% to below 7.5% as share of personal income, and, in passing, to the size of President Obama's stimulus programme in 2009. What the left hand giveth, the right hand taketh away.

Since taking mumps away from the economy is not a practical solution, especially when the private sector refuses to spend, it stands to reason that the government must spend on behalf of the economy instead.

As Magnus argues, this is largely about recognising that one does not detract from the other, and that it's not a question of 'either-or':

But moving on, the second is that if central banks can't re-energise sustainable economic growth or tackle structural economic weaknesses, governments should. But this entails their switching tack to implement both demand-side and supplyside policies, and not treat them as an 'either-or' choice. This is common sense because the economic gains from structural reforms are medium- to long-term, while the pain they inflict is up front. To compensate, and give structural policies stronger political legitimacy and a chance to succeed, demand-side fiscal changes are needed too, in particular those that aim to raise employment and labour force participation rates. Most advanced economies face this challenge, not least the US as the so-called fiscal cliff looms, but in the Eurozone, it has become critical.

To Europe's political class he thus states:

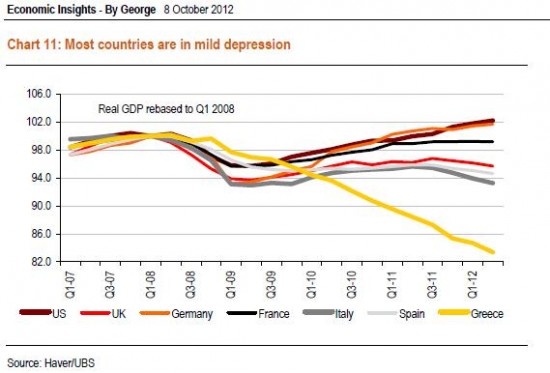

Politicians still don't get it: in spite of some rhetoric regarding the need for growth since the election of President Hollande in France earlier this year, not everyone can save more at the same time without perpetuating or deepening the depression. In such an environment, governments need to accommodate the deleveraging and additional savings of the private sector, not exacerbate them. And while some sovereign invalid nations have no option but to make painful fiscal cutbacks, they should be allowed and encouraged to do this not as caseby- case, errant countries, but in the context of a) a holistic approach to economic policy making in the Eurozone, involving creditors, and wider use of debt restructuring or relief arrangements, and b) a banking and fiscal union, which will require debtor, and especially creditor, nations to take a deep breath, and give up their political sovereignty.

We feel the point here is that yes, structural reforms have to be taken in many European countries. However, the sooner the world realises that the old debt rules don't necessarily apply to economies that to this day cannot justify delayed consumption — because there is more than enough capacity and output to go round, and there is no need to consume less today in order to ensure more output tomorrow — there isn't the same importance attached to ensuring that old investor promises are kept sacrosanct.

After all, it may not be the case that the economy has failed to provide the additional output investors were promised and that there is thus a scramble over a small amount of goods — something that would have given those who held promises "to more output" a clear advantage in society (making those promises extremely valuable). In those circumstances, the unexpected cancellation of promises would naturally lead to someone, at some point, having had to go without.

What we are arguing instead is that today that's not the case, and that tangible output has most likely exceeded expectations. So whether you hold a promise or not is largely irrelevant. The promise is part of a semantic debate over the quantitative value of the promises, rather than the goods which are redeemable with them. After all, what does the number of promises in the economy matter, when there is more than enough goods and services to go round? In this scenario, cancelling the promise allows the economy to reset the allocation system of the wealth that's freely available — it does not, however, result in someone at any point having to go without.

The reset is about consuming what is available today — stopping it from going to waste — and, most importantly, creating a more sensible wealth allocation system for a future that is far too productive for its own good. It's not about promising more to those who delay consumption today for the sake of more output tomorrow, but rather rewarding those who don't consume enough today with the ability to do so — perhaps in this curbing the inequality gap. That's not to say all investment becomes futile, because there has to be a reward distributed to those who dedicate current consumption towards efficiencies that will keep improving the standard of life for all, but without posing an additional burden on resources.

But perhaps that's what the crisis is about? Figuring out how people can be incentivised to keep improving the world, in an environment that no longer requires people to go without to get stuff done.

Owning an equity stake in the business that employs you *might* be one way around it. Then again, so might moving towards a more equity-based currency exchange system. Who knows.

Related links:

Corporate margins reaching record levels – FT

Rubik's Revolutions - FT Alphaville

Don't call it money printing, rubik's cube edition - FT Alphaville

A time of hoarding and inflation fears, 1930s edition – FT Alphaville

Is unlimited growth a thing of the past? – FT

Sent from my iPad

No comments:

Post a Comment